- POPSUGAR Australia

- Beauty

- De-Influencing Is Trending, But Do TikTok Influencers Actually Want Us to Stop Shopping?

De-Influencing Is Trending, But Do TikTok Influencers Actually Want Us to Stop Shopping?

In a post with over 4 million views, influencer @alyssastephanie says, “I love the de-influencing trend, here are some things I’ll de-influence you from buying, as someone who spends thousands of dollars on beauty and wellness products a year but loves to save a buck.” Alyssa goes on to slam thousands of dollars worth of prestige hair, makeup and skincare products, providing cheaper alternatives for each one.

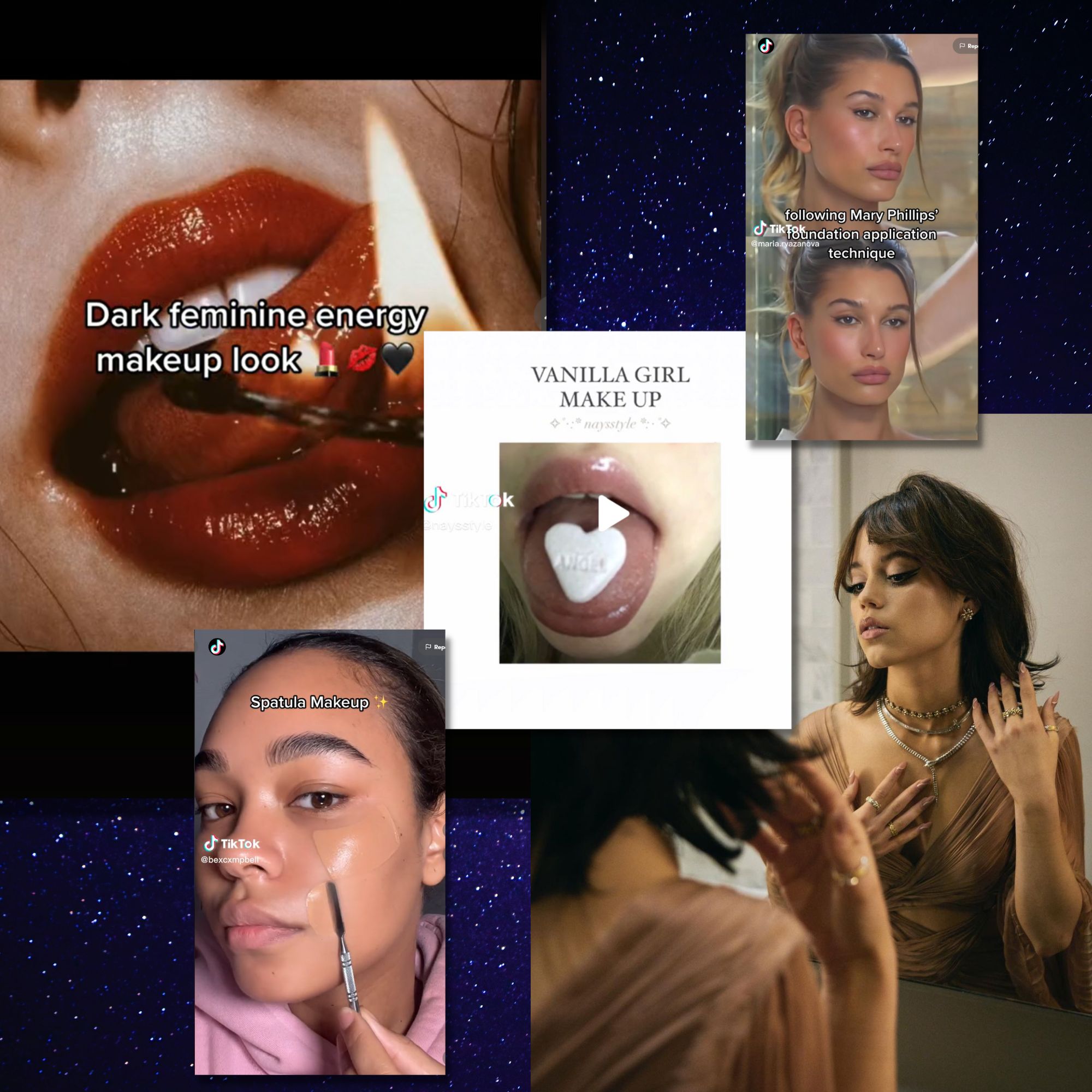

TikTok’s latest trend is giving us whiplash: it’s called “de-influencing”, it has 43.9 million views on the platform, and it’s seeing TikTokers tell us the products we should be ditching and dropping in the beauty aisle.

Influencers are not only telling us to skip products, they’re dragging them. Cult beauty products are described as “horrible”. An influencer called @Katiehub.org describes a TikTok-popular luxury brand as “pretty packaging over garbage”.

It’s scalding, somewhat thrilling, and downright derogatory tea.

Over the last few years, the platform has become a rubber stamp for beauty products, old and new, that will sell out in seconds. So, why are we being told not to buy?

@alyssastephanie I love deinfluencing ❤️ #deinfluencing #deinfluencergang #cultproduct ♬ original sound – Alyssa ✨

Why We’re Being De-Influenced

Dr Brittany Ferdinands is a lifestyle creator and academic who researches the influencer economy. She tells POPSUGAR Australia that TikTok was a massive disruptor in the influencer landscape. “Compared to Instagram, which has a capitalist-style algorithm, anyone on TikTok can technically go viral and produce a video that attracts a million views.” This has encouraged a view that TikTok is more “authentic” than Instagram. But, four years in and a few scandals later, influencers are struggling to maintain credibility.

According to Dr Ferdinands, it’s this credibility that’s essential for influencers looking to make a living in the $16 billion creator economy. Paradoxically, to do this they need to play down the extent to which the TikTok trend machine is a money-making machine that they’re a part of.

“Influencers deploy authenticity to downplay the economic factors,” she explains. “It’s carefully choreographed and a strategic form of self-presentation that establishes consumer relationships.”

Ferdinands says de-influencing is popping off as consumers get savvier. “Trust is everything for an influencer,” she explains, “the more critical they are in their product recommendations, the more likely their content will be received as ‘word-of-mouth advertising’ which, in the long run, results in a more engaged audience. A more engaged audience leads to more revenue because engagement is what advertisers are buying on the platform.”

Are Environmental Concerns Behind De-Influencing?

Sustainability is also placing pressure on brands and creators as consumer expectations shift. A survey commissioned by Global Cosmetics Industry found in June 2022, 64 per cent of consumers said sustainability was “very important” when considering the purchase of a beauty product, up from 58 per cent in 2018. If the same influencer is telling you to buy eight different blushes in the space of a month, you may start to think they don’t have the planet’s best interest at heart.

Maddy is a 26-year-old journalist, studying a Bachelor of Environmental Science part-time. She says that TikTok is a double-edged sword. “It gives me massive decision fatigue,” she says, and she struggles with balancing TikTok as a resource, with its environmental impacts. “Whether I’m looking for products for curly hair, or picking up skincare tips, TikTok is a great resource, but I do find the constant product recommendations jarring when you consider the reach of the platform and the environmental implications of overconsumption.”

@katiehub.org Replying to @.sam_ross THIS MIGHT BE A HOT TAKE HAHA #fyp #deinfluencing #dior ♬ original sound – katie

For Heather, a 34-year-old mother of two, TikTok has caused a beauty relapse she’s conflicted about. Despite years of working in the beauty industry and advertising, she’s obsessed with shopping the platform. “Years after leaving beauty and advertising, my makeup collection almost started looking like something reasonable for one person,” she tells POPSUGAR Australia.

“Then I found my perfect micro-influencers on TikTok,” she says these influencers seem to genuinely appreciate the magic of makeup. “It reminded me why I first fell into the industry and woke up my love for it again.” However, Heather now has 12 liquid blushers, 6 cream bronzers and “too many shadow sticks on the go”. She’s also worried about waste. “I’m now encountering the old familiar feeling of loving something with an expiry date that will eventually end up in the bin. It’s at odds with my priorities and values around sustainability.”

Emma Lewisham, founder of leading sustainable beauty brand Emma Lewisham, says the TikTok trend cycle also has a serious impact on beauty businesses, which struggle to do the right thing when potentially any new product could go viral. “Trend-driven product launches have a ripple effect,” Lewisham tells POPSUGAR Australia, “constantly releasing new products contributes to waste.” This waste, Lewisham tells us, contributes to 120 billion units of packaging a year, the majority of which, although technically recyclable, will end up in landfill. It’s also bad for the beauty industry and the consumer, who ends up with less effective products.

“[When you’re] constantly releasing new products to keep up with trends, this creates higher operational costs – and diverts employee’s attention to the next best thing, when resources could be better spent investing in enhancing and improving the current range.”

Is De-Influencing All About Cozzie Lives?

Notably, for every product Alyssa pans, there’s a cheaper alternative. A $60 blush is replaced by a $25 one. A $900 hair tool is replaced by a $30 Amazon dupe. It’s generally expensive products being panned and dragged, which, even as a beauty journalist, results in a certain level of schadenfreude.

Ferdinands says the nose-dive the economy has taken is playing a role here. “Consumers are being more judicious with their spending,” she says “and there’s been pushback against influencers flouting their wealth with rising cost of living.” Again, for Ferdinands, it comes back to the struggle for influencers to maintain reliability.

Related: The “Boring Manicure” Caps Off 2022, the Year of The “Non-Trend”

Significantly, Alyssa specifies that she spends “thousands of dollars a year” on beauty products. With over 600,000 products, it’s safe to assume that Alyssa is also receiving hundreds of gifted products a year, a necessity for any beauty influencer or beauty journalist, but something many consumers don’t understand when they’re absorbing product recommendations. Yes, a product may be wonderful, but has the person recommending it had to shell out for it?

Hannah English, one of Australia’s most respected skincare and beauty influencers, says in an ideal world, deinfluencing wouldn’t be necessary, because influencers should be helping consumers make smart decisions. “I’m fortunate I have good relationships with my favourite brands,” she says, “I can talk about new releases, or my old favourites and not just random products.” She says she doesn’t feel pressure to talk about products for money, and will always use and trial before recommending. What she has noticed is a shift in expectations from consumers, who want more from creators, and it’s no longer about just deciding what to buy. “People will always look for help deciphering product claims, and help using products, fitting them into their lifestyle,” she says, in this context, “influencers should be more curators in their field.”

Is De-Influencing the End of Influencing?

In this editor’s opinion? Probs not.

Alyssa’s video is the number one video under the #deinfluence hashtag, with 609.5k views and over 5k comments, the first being “Ugh, this trend influences me even more.” Advertiser gold.

Herein lies the problem with de-influencing as a concept, influencers still need something to talk about, and cheaper brands, often owned by the same multi-nationals that produce expensive ones, can still pay the bills.